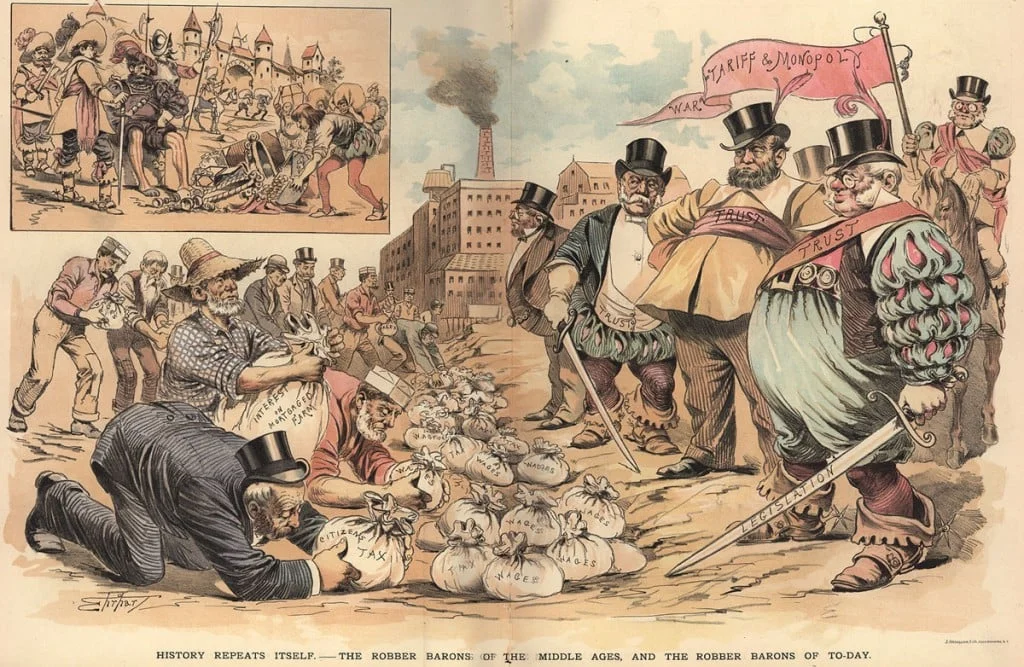

THE INVISIBLE HAND

The invisible hand was a metaphor used by Adam Smith to describe the unintended social benefits resulting from individual actions. He used the term with respect to income distribution and production. The exact words “the invisible hand” was used just three times in Smith's writings, but an expansive interpretation of this concept is now beloved by large corporations, all manner of right wing politicians, Ayn Rand nuts, and idiots from the Chicago School of Economics who have applied the hand to developing nations with disastrous results. The theory can be summarized as follows: an individual's effort to pursue his own interests frequently benefits society more than if he tried to do something with an intent to benefit society. In other words, let me be greedy because you all will benefit.

Present day “invisible hand” adherents believe that if each consumer is allowed to choose freely what to buy, and each producer is allowed to choose freely what to sell and how to produce it, the market will settle on product distribution and prices that are beneficial to all the individual members of a community, and hence to the community as a whole. Efficient methods of production will be adopted to maximize profits. Low prices will be charged to maximize revenue because the cheapest and the best producer will gain in market share by undercutting similar competitors. Further, invisible hand believers argue, investors will invest in those industries most urgently needed to maximize returns, and withdraw capital from those less efficient in creating value. All these outcomes will somehow take place dynamically and automatically.

Not surprisingly, few metaphors have so captured the American psyche. Those who are wealthy have little to gain from economic interference. No matter how greedy and selfish they are, they can insist that they’re helping society at large. Furthermore, the cultural impact of this vision of the invisible hand serves to reassure those who are poor, making the point that by looking out for themselves they can get ahead and work towards the greater good simultaneously! There’s no need to rely, invisible hand believers argue, on the concerted efforts of government or church to direct commercial activity. Since the proper economic and legal institutions have already been set up, it’ll all turn out better if corporations are left to tehir own devices. Don’t change a fucking thing! And not only that, simply by looking out for ourselves, we work towards the greater good! Because of the invisible hand, we have no moral obligation to look beyond our own interests.

Unfortunately, history disproves the notion. When Smith first referenced the invisible hand, slavery was an important element of capitalist economy. Nothing in the invisible hand abolished slavery. In fact, the free market proved both incapable and unwilling to provide racial economic justice. Likewise, both large corporations and small businesses took no steps toward gender equality absent government interference. In fact, many economists now argue that while markets may be somewhat effective at allocating resources where they are most needed, there are so many exceptions to the rule of the invisible hand that the exceptions deserve more attention as the rule itself. For example, Jeff Madrick, Director of the Bernard L. Schwartz Rediscovering Government Initiative, and a Senior Fellow at The Century Foundation, calls the “invisible hand” one of the “seven bad ideas” of mainstream economics that “have damaged America and the world.” [1]

The concept of an invisible hand rests on four “rationalist”assumptions: (1) People are rational; (2) Most businesses are honest; (3) The consumer and the seller meet in the open market to negotiate the best deal possible for the consumer. (4) The consumer can decide for himself or herself what they need and what they want. But when rationialist assumptions are examined rationally, it becomes apparent the theory of an invisible hand rests on sand. Indeed, its real purpose of the invisible hand serves to hide, not clarify, the economic injustices and ecological waste generated by our way life.

False Assumption No 1. People are rational.

Many consumers are overconfident, react to emotions not facts, and respond poorly to crisis. They also display "irrational exuberance" (unrealistic goals and plans); "present bias" (not planning for the future); and are prone to "loss aversion" (disliking losses even when losses are part of the process to achieve a fair return on their money).[2]

“Oh tell me, who first announced, who was the first to proclaim that man does dirty only because he doesn’t know his real interests, and that were he to be enlightened, were his eyes to be opened to his real, normal interests, man would immediately stop doing dirty, would immediately become good and noble, because, being enlightened and understanding his real profit, he would see his real profit precisely in the good, and it’s common knowledge that no man can act knowingly against his own profit, out of necessity, so to speak . . . What is to be done with the millions of facts testifying how people knowingly, that is, fully understanding their real profit, would put it in second place and throw themselves onto another path, a risk, a perchance, not compelled by anyone or anything, but precisely as if they simply did not want the designated path, and stubbornly, willfully pushed off onto another one, difficult, absurd, searching for it all but in the dark . . . And what if it so happens that on occasion man’s profit not only may but precisely must consist in sometimes wishing what is bad for himself, and not what is profitable? . . . But here is the surprising thing: how does it happen that all these statistician, sages, and lovers of mankind, in calculating human profits, constantly omit one profit? They don’t even take it into account in the way it ought to be taken, and yet the whole account depends on that. . . this one most profitable profit . . . which is chiefer and more profitable than all other profits, and for which a man is ready, if need be, to go against all laws, that is, against reason, honor, peace, prosperity—in short, against all these beautiful and use things—only so as to attain this primary, most profitable profit which is dearer to him that anything else. . . [M]an, whoever he might be, has always and everywhere liked to act as he wants, and not at all as reason and profit dictate . . . One’s own free and voluntary wanting, one’s own caprice, however wild, one’s own fancy, though chafed sometimes to the point of madness—all this is that same most profitable profit, the omitted one, and because of which all systems and theories are constantly blown to the devil.” [3]

False Assumption No. 2. Most companies are honest.

Even true believers of the invisible hand will admit that some companies may attempt to unduly influence potential customers by deceptive advertising, manipulating emotions, or outright cheating. Nevertheless, they argue, limited misconduct is acceptable, because companies that lie will not last long. Furthermore, if deception rises to the level of fraud and customers are hurt, the law will intervene (an argument which contradicts the very premise of the invisible hand - leave corporations alone!). However, all corporations exploit human weaknesses, not necessarily because they are malicious (although some are) but because the market makes them do it. In reality, cheating companies prosper because the law is stacked against the consumer. Furthermore, if a company does not actively seek to take advantage of the consumer, the company will fail. Watch any commercial on television or social media. Dear reader, do yu really believe that Chevron Oil is working to improve the environment, or that Fan Duel wagering will make you rich, or that this year’s Chevrolet-Ford-Toyota-GMC truck is the toughest, or that fast food is not only cheap but also good for you?

False Assumption No. 3.

The consumer and the seller meet in the open market to negotiate the best deal possible for the consumer. No one has to buy any product or service.

Banks, retailers, drug companies, real estate agents and vice producers (vaping & cigarettes, porn, liquor, marijuana) "angle" the consumers utilizing a wide variety of means, including but not limited to deceptive advertising and psychological manipulation. Many corporations convince consumers to enter into sales relationships that are in the best interest of the vendor, not to the consumer. Do you believe that the current rates of alcoholism, drug addiction, obesity, depression, sexual disfunction, and excessive household debt are the results of rational decisions make by consumers negotiating in a equal and honest market? Of course not, the invisible hand guarantees this form of angling. Imagine a cigarette company warning you that their product may kill you, or a bank refusing to grant you a credit card because the interest rate is too high, or an oil company admitting that carbon pollution is destroying life on Earth, or a loan officer stating that, in the long run, you won't be able to afford the home you want and that its value will fall significantly during the next recession.

False Assumption No. 4.

The consumer can decide for himself or herself what they need and what they want.

"Needs" are created by the market, not by consumer. For example, if a woman want's to obtain a well paying clerical job, she must dress and live in conformity to her employer's and co-workers' standards. The invisible hand forces certain levels of consumption before a consumer earns the privilege of working.

As mentioned above, some economists simply don’t believe that the invisible hand even exists. For example, Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph E. Stiglitz, says: "the reason that the invisible hand often seems invisible is that it is often not there." He explains his position as follows:

“Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, is often cited as arguing for the "invisible hand" and free markets: firms, in the pursuit of profits, are led, as if by an invisible hand, to do what is best for the world. But unlike his followers, Adam Smith was aware of some of the limitations of free markets, and research since then has further clarified why free markets, by themselves, often do not lead to what is best. As I put it in my new book, Making Globalization Work, the reason that the invisible hand often seems invisible is that it is often not there. Whenever there are "externalities"—where the actions of an individual have impacts on others for which they do not pay, or for which they are not compensated—markets will not work well. Some of the important instances have long understood environmental externalities. Markets, by themselves, produce too much pollution. Markets, by themselves, also produce too little basic research. (The government was responsible for financing most of the important scientific breakthroughs, including the internet and the first telegraph line, and many bio-tech advances.) But recent research has shown that these externalities are pervasive, whenever there is imperfect information or imperfect risk markets—that is always. Government plays an important role in banking and securities regulation, and a host of other areas: some regulation is required to make markets work. Government is needed, almost all would agree, at a minimum to enforce contracts and property rights. The real debate today is about finding the right balance between the market and government (and the third "sector" – governmental non-profit organizations.) Both are needed. They can each complement each other. This balance differs from time to time and place to place.” [4]

Mr. Stiglitz’s well-reasoned argument, unfortunately, doesn’t go far enough. Although the corporatist notion of some form of helping hand (an invisible one that allows each of us to be as greedy as we want so the common good will benefit) is patently false, there is something out there, make no mistake about it.

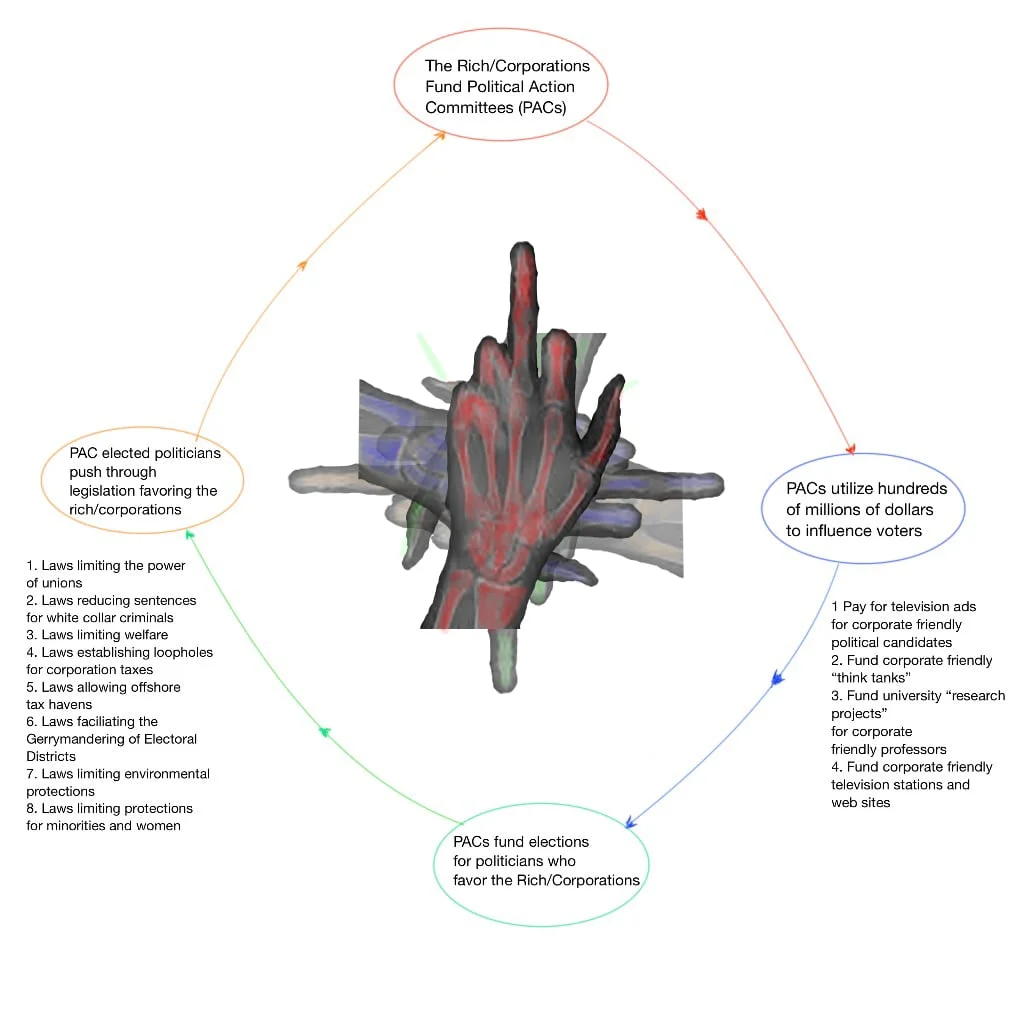

And it intrudes on every aspect of our lives. A big, thick, wagging index finger that says “fuck you” to all but the rich, a finger that serves the wealthy and powerful while simultaneously working to screw those of us who are working or poor, a big-finger is either invisible or visible, depending on whether you’re one of the swells or not. Here’s how it works.

[1] Daniel Altman. Managing Globalization. In: Q & Answers with Joseph E. Stiglitz, Columbia University and the International Herald Tribune, October 11, 2006. See also, Jonathan Schlefer, There is no Invisible Hand, Harvard Business Review, April 10, 2012.

[2] See Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception. George A. Akeroff and Robert J. Shiller, Princeton University Press, 2015

[3] Notes from the Underground, Fydor Dostoevsky

[4] Jeff Madrick, Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present, Vintage; Reprint edition (June 12, 2012).